Latest Posts by caitlin-mcc03 - Page 2

Steve Tobin

The “GLASS LANTERN HOUSE” 6w x 8d x 11h is made from 100+ year-old hand-tinted glass slides for projection. They reflect a time when every photo was made to perfection and craftsmanship was old world, made with enduring values. The house has a peaked roof like a church. All of the world’s cultures and values are contained in this house of humanity as one. With a projection bulb inside the house, you can fill a room with these archival images of a time before now.

Ana Vieira

Ana Vieira’s work is deeply concerned with the body, space, and the ways in which art is sanctified and received. Her artistic career spans multiple disciplines, including theatre, painting, sculpture, photography, sound, environment, and installation. This breadth reflects her poetic approach to art, which continually explores the boundaries of different media.

Her exhibitions, starting in 1968, highlight the themes of her work through their titles, such as Imagens Ausentes (Absent Images) and Ambiente (Milieu). These exhibitions examine dichotomies like public/private, presence/absence, interior/exterior, and transparency/opacity. For example, in one installation, a dining room scene is set up with plates, cutlery, and glasses, but the viewers cannot see it. They hear sounds from the space, but are kept at a distance by a mesh, reinforcing the separation between the public and the private.

Vieira's scenography often features elements like cut-out silhouettes, projections, hidden objects, and revealed rooms. These works extend beyond galleries into public spaces and even the natural landscapes of the Azores, her hometown. As her works expand in scale, they invite the viewer to physically engage with and inhabit the spaces, making the viewer’s body a part of the art experience.

DINING ROOM, ENVIRONMENT (1971), WOMEN HOUSE EXHIBITION, MONNAIE DE PARIS, FRANCE . 2017/2018

MILO'S VENUS, ENVIRONMENT (1972)

WINDOWS . 1978

Heidi Bucher

Heidi Bucher: Beyond the Skins at Red Brick Art Museum, 2023

“Rooms are shells, they are skins.”

Heidi Bucher: Beyond the Skins at Brick Art Museum, 2023

Heidi has codified the method of skinning, and further explored the possibilities of the act in various spaces. The attribute of the chosen spaces has witnessed a gradual transition from intimate to family history, and even historical and is loaded with public memories.

In Heidi’s works, history, memory and emotion acquire a new, linguistically inaccessible imagery. As Gaston Bachelard puts it in The Poetics of Space, “When we have been made aware of a rhythm analysis by moving from a concentrated to an expanded house, the oscillations reverberate and grow louder. Like SupervielIe, great dreamers profess intimacy with the world. They learned this intimacy, however, meditating on the house.” As one receives a new poetic image, an emotion is re-spoken, the poetic reverberation is taking place in the inner space of consciousness, and the house – at Heidi’s request – “has to fly”; “It has to get away, far away from reality.”

Deirdre Frost

Áitreabh 2021, oil and acrylic on birch panels attached together with lift-off hinges, approx. 350 x 300 cm.

Baile 2021, Oil on board, 80 cm x 120 cm.

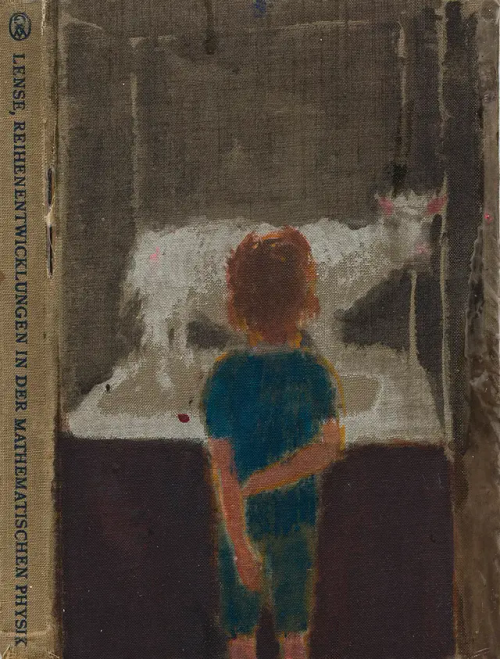

Andrew Cranston

Aberdeen Studio (My Blue Period), 2023, distemper on canvas, 212.9 x 182.4 cm, 83 7/8 x 71 3/4 in

Andrew Cranston’s figurative paintings are steeped in atmosphere; their fragments of narrative quickly dissolving into dreamlike visions of objects awash in colour, shape and texture. His works often depict domestic interior spaces – in a not-so-distant echo of the arrangements of classical still lives – but where such ordinary things as windows, items of furniture, and ornaments become conduits for far more uncanny formal explorations. Abandoned tables, libraries, tents and private chambers are just some of the scenes in which Cranston’s expansive imagination takes shape, drawing from his lifelong interest in storytelling through colour and form. His works take two distinct formats: large scale canvases worked in distemper and oil, and smaller paintings executed directly on hardback book covers. Often his paintings revel in a single colour field, whether oceanic blues, ruddy ochres, or blazing scarlets, within which his dreamlike worlds unfurl through the expressive treatment of surfaces. Their atmospheres flicker between the private and the theatrical, the picturesque and the chaotic, abundance and solitude, each in their own way beckoning the viewer deeper into their worlds.

Rudy and Dolly, 2024, oil on hardback book cover, 23 x 17.2 cm, 9 x 6 3/4 in

Stay with me, my nerves are bad tonight, the midges too, 2022, distemper and oil on canvas, 170.3 x 130.2 cm 67 1/8 x 51 1/4 in

Losel Yauch

Yauch focuses on sheer materials and the shape of light as a visual tool to communicate the feeling of loss and examine the presence of absence, fragility of form, and on a broader scale, the concept of grief. Her paintings articulate subtle yet considered distinctions between the intangible and the out of reach.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Splitting, and the Unmade House

Matta-Clark understood the emotional impact buildings have on people. In a 1976 notebook entry, he expressed his goal to “transform a location into a mental state.” This link between a home and its residents was reflected in the letters he received after the reveal of Splitting.

Although the home was viewed as a private space, families were also urged to participate in neighborhood networks that valued conformity. These connections were presented as key to the "good life." Matta-Clark examined the motivations behind the creation and promotion of this ideal, questioning whose interests it truly served.

Instead of viewing architecture as a solution to housing issues—having witnessed the effects of post-war developments first-hand—Matta-Clark used architecture as a medium for sculpture, bringing the cuts of buildings to life in his photographs. The act of transforming abandoned buildings and documenting the process was central to his practice, as was the social commentary expressed through the boldness of these transformative actions.

Enrica Casentini

Open Doors

The door is a symbol of border, of passage from a dimension to another one, from inside to outside.It can be open or closed.From the door to the house, an intimate space of identification, from house to city, extensive space of passage or stay where peoples, races and religions live together.Sometimes it's more difficult to open own doors. In this work I wanted to represent the individual and his will to open. Houses, like individuals, are many and different from each other. All doors are open to signify the choice of every individual, they rapesent the human will to open to exchange. For this reason the title of my work is "the open doors", it's my strong opinion that doors and borders can became place of exchange not of division.

You pile up associations the way you pile up bricks. Memory itself is a form of architecture.

Louise Bourgeois

thoughts on memory

louise bourgeois / aftersun (2022) / joan didion / phoebe bridgers / carmen maria machado / st vincent / lisa ko

Arturo Kameya

Pan y circo, pero circo sin pan, 2020, Acrylic and clay powder on wood and found objects, installation approx: 270 x 450 x 20 cm | 106 1/4 x 177 1/8 x 7 7/8 in

"Childhood memories, scenes from Lima’s suburbs where the artist grew up in the 1990s, family traditions and popular culture often form the point of departure of Arturo’s artworks. These sources lead to intriguing groups of related, finely detailed paintings, installations and, occasionally, videos. [...] Arturo’s work feels both familiar and unknown at the same time. Yet all elements seem to relate. They find each other in a carefully composed idiom constructed by gentle looking forms and by soft pastel and grayish, slightly muted, colors. [...] Arturo’s artworks may looklike mementos or witnesses from a bygone era, which addssomething bittersweet, in between nostalgia, a painful sentimentand a celebration of the past." - excerpt from Turning history downside up by Madelon van Schie, Who can afford to feed more ghosts, 2021

Acrylic and clay powder on wood, wooden stool and tarantula skin, 70 x 82 x 25 cm | 27 1/2 x 32 1/4 x 9 7/8 in

Silencio sísmico, 2022, Acrylic and clay powder on wood, canvas and found objects, Variable dimensions

Celina Vleugels

How Can I become You series, 2019, Acrylic and embroidery on different fabrics

To the Temple of Childhood Memories, 2021, jacquard piece of an oil pastel drawing, wool and linen, 120 x 170 cm unique

Even when the season changes, you will always be rememembered. 2020, Industrial weaving combined with hand embroidery pieces 128cm x 145cm

Koh Myung Keun

Hong Kong 12-1 (Edition 3), 2012, 66 x 44 x 20 cm, Digital film 3D-collage, plastic.

Koh uses photography, a two-dimensional medium, but transforms it into a three dimensional piece with a unique technique. Koh makes digital prints of his photos onto film, which he then laminates with clear plastic, and constructs into three-dimensional forms using a heat gun. The semi-transparent photographic layers have been constructed as if they were the walls of a building, but not as an attempt to recreate the structure of the subject. What we see is a paradoxical space, where the interior seems to be the exterior itself. Koh has been using this method since the 1980’s, creating series based on three main subjects: nature, architecture, and the figure.

Beijing 09- 4 (Edition 3), 2013, 86 x 43 x 12 cm, Digital film 3D-collage, plastic.

Emma Parker

“My work explores the darker and often hidden aspects of being human: fear, shame, abandonment, despair and the broken – with an occasional twist of humour added for sanity. I use discarded and worn materials in my work and see the act of making with them as a process of transformation and salvaging of the broken self."

“The use of thread and stitch helps me make connections and piece the broken together whilst the repetitive nature of hand sewing is a soothing rhythm, which nurtures and helps mend. In my work I often include fragments of narratives or imagery that may tell only part of a story, leaving it up to the viewer to find their own ending.”

Martha Naranjo Sandoval, Petén 411, 2016-2017

Paper collages. C-prints, archival tape.

JoAnne Lobotsky

The work is based on a fragment of an idea and then developed intuitively and organically during the process. My work is autobiographical in that I try to express the feeling I have of the time and place I grew up in. Things being reused and repurposed as well as things being jerry-rigged were typical on a small mid-century farm. Imperfection, abjectness and roughness coinciding with beauty and a kind of humble elegance are my main goals. I use mostly scraps of fabric that have a history of use by other people and there is sometimes damage from wear or stains that I embrace. Other types of materials are used that suggest fur, bark or vegetation. I feel that my approach to this work which involves imperfection and roughness is also in some way a rebellion against our class system and economic entitlement and strives to become accepted on its own terms within its own limitations. My work has roots in the Arte Povera movement in the commonplace and worn materials I use which present a challenge to established notions of value and propriety.

What Remains, 2019, Canvas, acrylic, fabric, thread, wood, feather, bleach, paper, clothes pin, antique nails on canvas, 23 X 34.5"

Where I'm From, 2019, Canvas, fabric, embroidery, cheesecloth, micaceous iron oxide, feathers, faux fur, tatting, antique buttons. Some areas are lightly stuffed. 23 X 58 X .5"

Alexa Meyerman

10:25 AM, inkjet : transparency film, 15 x 20 x 15 cm, 2010

This work is based on architectural deconstructions. Like in memories or dreams, every part is reconstructed, leaving an impression of unplanned reality. In some of the work there may be traces of human presence, but they are all empty, or temporarily abandoned. Anything could happen, but nothing does, besides the soundless shifting of elements in a bare, changing and undefined volume. In this way architecture transforms into anarchy of space. You can wander -not hide- in these idle constructions which, in the end, only consist of a rhythm between light and darkness.

11:25 AM, inkjet : transparency film, 29 x 21 x 15 cm, 2011 The transparent photo-objects can be seen as deconstructions. In spite of traces of human presense, what these models have in common is that they are either empty or temporarily abandoned. Like in memories or dreams, the buildings are reconstructed, some details have been emphasised others are dissolving or dissolved. The concepts of interior and exterior become interchangeable. One can look in and around the objects, and then they will transform, depending on the incidence of light or point of view, which results in the appearance, or disappearance of exits, entrances or rooms. Unavoidably you have to approach the buildings closely, but you cannot hide in these idle constructions, which after all in the end, only consist of light and darkness.

Ghost Buildings

"It’s short of a shared tone of memory that’s left like breath on a mirror."

Lyon, France

Newcastle Upon Tyne, England

"Is it the fear of forgetting that triggers the desire to remember, or is it perhaps the other way around?" (Andreas Huyssen, Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory, 2003)

Chiharu Shiota

"Everything I create is from a personal experience but I want to extend it into something universal." Stepping into one of Chiharu Shiota’s striking installations is like entering an alternate reality: the materials and objects feel familiar, but the logic behind the intricate web structures seem to stem from an unknowable realm. Enveloped in an elaborate web of yarn, you’re left with a subtle, indescribable imprint on the body and mind.

The Key in the Hand, 2015. Installation: old keys, wooden boats, red wool. Japan Pavilion at 56th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy For the 56th Venice Biennale, Shiota unveiled ‘The Key in the Hand' (2015), a piece created for the Japanese pavilion. In this installation, 180,000 keys gathered through an open call were suspended from dense webs of red yarn, which linked the gallery space to two wooden boats on the floor. A photograph of a child holding a key was displayed alongside four monitors featuring videos of young children talking about memories before and after they were born. For the artist, keys are a personal object that simultaneously keeps our space safe on a daily basis and has the potential to unlock doors to new, unknown worlds. The keys dangling from thousands of red strings evoked a sense of intercon-nectedness and expansiveness, allowing viewers to imbue their own memories and associations to the familiar everyday item.

Counting Memories, 2019. Installation: wooden desks, chairs, paper, black wool. Muzeum Śląskie w Katowicach, Katowice, Poland For ‘Counting Memories’ (2019), an installation shown at Muzeum Śląskie in Katowice, Poland, the artist envisioned a network of black yarn extending from the ceiling to be a night sky, or a universe, filled with white numbers dotting the space like stars. The piece invited viewers to sit at desks (also entangled in black yarn) where they had the opportunity to answer questions and contemplate the significance of numbers in their lives: Numbers that have special meaning, numbers in the form of dates, numbers connected to personal histories. As with many of her works, the installation attempted to make visible the invisible threads shaping our inner and outer lives.

Chiharu Shiota – A Room of Memorya, 2009, old wooden windows, group exhibition Hundred Stories about Love, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan

Booster and 7 studies series / Autobiography, Robert Rauschenberg, 1967-68

Niklas Roy

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2020/02/niklas-roy-little-piece-privacy/

Berlin-based artist Niklas Roy isn’t just concerned about his privacy and protection online. To stop passersby from peeping into his workshop, he strung up a white, lace curtain stretching only partially across his window. Titled “My Little Piece of Privacy,” the ironic project from 2010 was established to offer seclusion to the artist, while recording those who walked past his space. Each outside movement triggers a motor to position the thin fabric in front of the person attempting to look inside.

Paul Sermon

The bed is an object that is understood in all social and cultural contexts. Its semiotic language vary from the childhood context of security and play to the more complex context of privacy, intimacy and relaxation. When such a "charged" object is used as a telematic interface the user is confronted by the complexity of the object/interface and not the complexity of the technology. The telematic experience of communication is heightened when the technology involved is secondary to the primary point of importance, the bed interface. The technology disappears and becomes invisible. The bed is a very intensive object. The users are sometimes reluctant to enter "Telematic Dreaming", not because of the video technology, but because of the potential interaction on the bed in the public space.

Selva Aparicio

“I presented this installation as my thesis during my MFA at Yale University,” Aparicio explains to My Modern Met. “Rugs are typically adorned with sacred gardens and oases, and can be moved around the home. This rug stayed put, quietly participating in years of familial abuse. This installation is about covering and exposing, trauma, and bearing witness.

Childhood Memories, 2017, hand carved rug into utility oak floor, (Total Installation 657 sq. ft.)

“My memories are permanently etched, so the soft fabric is represented in hand-carved scars on discarded wood flooring,” Aparicio continues. “I strive to find beauty in the peril and bear witness to the progression of ephemerality-permanence-loss.”

Clarissa Sligh

Reframing the Past (1984-1994) could also be titled Re-Reading the Family Album. From 1984 to 1994, Sligh’s work centred on a re-investigation and re-evaluation of her family’s photo album. Growing up in the blue collar, black neighbourhood of Halls Hill in Arlington, Virginia in the 1950’s, keeping up the family album was something the artist took great pride in. Not realizing that her early family album project was created through the lens of a stereotypical white American family, she saw the project as making a record of positive images of her black family.

She Sucked Her Thumb, 1989, cyanotype, 27.5 × 21.5 cm (10 13/16 × 8 7/16 in.)

Research on memory continues to unfold, but what we do know is that memory is fallible, and shockingly so. Most of our most cherished memories are confabulations, an intricate blend of fragments from our past, images from dreams, movies, books, and even other people’s memories assimilated as our own. This is the fantastic, frustrating, perplexing nature of memory: It is endlessly redefining and refining what we remember. Ask three siblings about a shared experience and you are likely to get three different versions of the event.

Our flawed memory unnerves us. We count on memory to validate reality. As our brains develop, we begin to create an autobiographical first-person narrative that defines who we are. Our identity formation depends on memories strung together into a recognizable story (autobiographical memory). In childhood, remembering positive choices and outcomes enhances a positive sense of self.

B. Ingrid Olson

This installation intermixes two series, Dura Pictures and Indexes. Each work in the Dura Pictures series presents one photographic image physically embedded within another, what the artist describes as placing a “moment in time within a different moment in time, just like memory does of the past in the present.”

Coming in with your back turned, 2021–2022, Inkjet print and UV-printed mat board in powder-coated aluminium frame, 29 × 19 1/4 × 1 1/4 in. (73.7 × 48.9 × 3.2 cm)

Completed Movement (Between Abut And Rub Between Two Notes The Number Between One And Two Divided Into Qualities And Kinds), 2016-2022 inkjet print and UV printed mat board in powder- coated aluminium frame, 96.5 x 45.72 x 3.2 cm 38 x 18 x 1.25 in

𝘕𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘳 𝘰𝘥𝘥 𝘰𝘳 𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘯 (𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘩𝘢𝘱𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘣𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘐 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘬 𝘐 𝘢𝘮 𝘣𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘪𝘴 𝘮𝘺 𝘰𝘸𝘯 𝘵𝘢𝘪𝘭), 2013-2020 Inkjet print and UV printed matboard in aluminum frame 14.5 x 12.5 in or 12.5 x 14.5 in (36.8 x 31.75 cm or 31.75 x 36.8 cm)